Interview by Stacia Levy

Stacia Levy: Dina is an interesting character, bicultural in that she easily navigates her traditional Native community as well as white, “Euro” society. How do you see this biculturalism shaping Dina and the story plot?

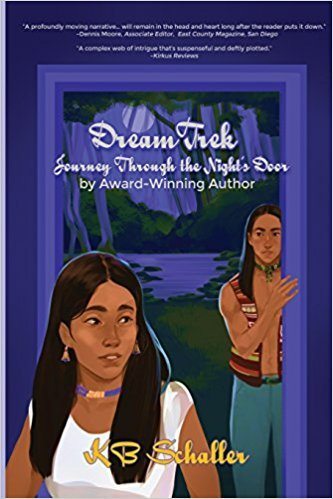

KB Shaller: I appreciate the opportunity to chat about DreamTrek: Journey Through the Night’s Door, third novel in the Journeyseries.Gray Rainbow Journey, the debut novel establishes Dina Youngblood as a young woman who continues the traditions of her Native American/Indigenous heritage culture: to respect and care for her elders and to allow the husband last word in matters.

DreamTrek finds now 21-year-old Dina, a former nursing student, married to 40ish Native evangelist Aaron Burning Rain, but still childless after two years. Her life takes a shocking turn when a stranger–who is somehow familiar–convinces her that a son by an earlier relationship–pronounced stillborn–is still alive.

Because Dina is familiar with the “white” world–more accurately stated, the increasingly multicultural society beyond her cloistered Bitterroot Confederacy of Indians community–she musters her courage and sets out in search of him.

SL: The character Dina often seems to take a submissive role to the people in her life. Do you see this as more cultural or individual? How so?

KBS: Dina’s submission is more to the tenets of her faith and her cultural belief in serving her family and community than giving in to any and every demand placed on her. Even as she is exposed to the two worlds, in Dina’s own words she states: “I’m proud of my heritage, proud to be Aaron’s wife, and I would give anything to have our children underfoot.”

Dina’s submission is also out of courtesy and respect for the counsel and wishes of her husband and Mama Hat, her always-opinionated, sometimes harshly critical, nearly a century old great-grandma. A firebrand at heart, it is sometimes a struggle for Dina to conform to their expectations. So, even as ‘voices’ tell Dina to calm down, take the easy path, play it safe, she must silence them if she is to find the truth regarding whether her son is alive or dead.

Within the confines of her culture, a truly submissive Dina, even in the strength of a mother’s love for her missing child, would not challenge tradition and the power it holds over so many.

SL: Dina defines herself, and her family, as Christian, followers of the Jesus Way, and religion plays a large role in her and her family’s life. How do you see the role of Christianity in the story?

KBS: It is erroneous to state that Dina defines her family as Jesus Way. A conspicuous example is her ambitious, self-centered younger sister who is not only determined to become the first Traditional Native American supermodel, but who also coaxes Dina to seek a similar career in the broader world.

Neither can it be said of Dina’s Aunt Lettie, the self-appointed family babysitter, who neither embraces nor disparages the Jesus Way, demonstrated in her tagline to visit church “someday to find out what this Jesus Way is all about.”

There are also instances in which neither Aaron nor Mama Hat believes Dina is “religious” enough, expressed when Mama Hat admonishes Dina, “Submit to your husband!” when Dina has ideas of her own; Dina further defies some of her great-grandma’s interpretations of Bible scriptures regarding the role of women, and criticizes Aaron’s “possessiveness.”

But believing she has a spiritual calling, Dina shares her faith with her familiars that the Jesus Way is not just “the white man’s religion” as most of Bitterroot’s denizens–and majority of real-life Native Americans–believe; when she finds them largely content in their traditional spirituality, even in her zeal, Dina respects their right to their beliefs.

In western culture, the Christian faith plays a role in all our lives to some degree, and as a believer married to a pastor, Dina chose the Jesus Way. But her “tainted” past and the possibility of finding her son compel her to flee the safe confines of Bitterroot and test her beliefs against some of life’s harshest situations and characters.

Her mettle is further “tested by fire” in a chance meeting with Marty, her childhood sweetheart. Now wealthy and famous, he makes her the offer not only of her son, but also if she will come with him, a life of glamour and indulgence. Dina must then decide what means the most to her–and what can be sacrificed.

SL: Abuse and exploitation play large roles in the novel. Nearly everyone is a victim and/or victimizer. The young Noccalula, the author of the journal, is an obvious example, victimized by many in her life, from her father to her child’s father to her adoptive parents. How does this theme of abuse and exploitation relate to the novel as a whole?

KBS: An acquaintance of mine who is an avid student of history as well as an aspiring author once stated that the history of European conquest in these lands have been almost entirely about abuse and exploitation of Native peoples.

He further commented, and I agree, that two camps exist in Native America: Those who want to maintain the ancient ways and those who wish to live outside [the confines of] the Rez and tradition.

Even as Native Americans continue to struggle with these enduring realities, there are also those who find common ground and navigate comfortably between the two. in DreamTrek< we see both victims and those who abuse; we also see an emerging new generation of characters who embrace fame and fortune with its glitz and allure–but also with its pitfalls and vices.

Because DreamTrek‘s characters view victims as those who willingly allow others to have total power over their lives, the majority of them, Dina included, live heroic lives as they face the challenges of both worlds.

Regarding young Noccalula, her circumstances are no more culture bound than occurrences we, unfortunately, see or read about in today’s mainstream news. Moreover, storytelling demands conflict. Drama. Action. Too, there’s consideration of the era in which Noccalula lived when practices such as men eating first and women last, and other customs we today would find detestable were considered the norm within the culture of her time.

SL: Dreams, diaries, and storytelling play a large role in the novel. Could you comment on how they relate to the novel thematically?

KBS: DreamTrek‘s characters and situations are largely used in an allegorical sense, representing the constant battle between good and evil.

The role storytelling, diaries and dreams play depends on the filter through which each reader interprets it: whether or not the story is perceived through a sense of adventure and expectation, through ingrained ideas–or even personal biases and feelings.

I can say objectively I think, that the thread propelling the story’s outcome is forgiveness–and whether or not characters can confront their own failures and circumstances, overcome them, and then move forward as they grow in wisdom and strength.

It is this author’s hope that readers considering the DreamTrek experience will allow its characters to tell their stories their own way and carry the reader into other times and places, where they will meet people whose lives differ from–yet are often strangely similar to–their own. And this author is very okay with that!

SL: This is the final book in the “Journey” series. What are your other plans for writing?

Through my characters, I will continue to allow those of Indigenous heritage who walk the Jesus Way—a minority within a minority—to tell their stories as I continue to promote DreamTrek.

Also on my short list of priorities are the continued promotion of Gray Rainbow Journey (Winner, National Best Books Award, multicultural fiction); Journey by the Sackcloth Moon, the sequel; and the nonfiction title, 100+ Native American Women Who Changed the World (Winner, International Book Award, women’s Issues). And, as one who values lifelong learning, to continue writing and growing in my craft.

READ our review of DreamTrek: Journey Through the Night’s Door.

KB SHALLER’s love for words developed in grade school after she wrote her first short story. Years later, she earned her master’s degree, served as cultural coordinator and art instructor in a reservation academy, and taught the learning disabled in public school—all while eking out time as a novelist and independent journalist.

Now a full-time writer, Schaller’s first novel, Gray Rainbow Journey (OakTara), set in a Native enclave in the Florida Everglades, won a coveted National Best Books Award, sponsored by USA Book News, was a finalist in two other categories, and was a number 3 Amazon fiction bestseller. The novel also won a 2011 Florida Publishers Association President’s Best Books Award for Young Adult Fiction.

Schaller has been profiled in Native Peoples magazine and the SunSentinel newspaper, has signed copies of her books at Santa Fe’s Institute of American Indian Arts and other venues, is often a featured speaker at conferences, and has been a guest on nationwide radio talk shows. Also a painter, she frequently creates character illustrations as part of her presentations.

Schaller lives in South Florida with her husband Jim, a design engineer, her mother Lilly, and the family’s two cats. “Chief,” a rescued stray from the Seminole Reservation, is the prototype for Gray Rainbow Journey’s feline character, “Eddie Was.” She is currently working on her third novel.

What people are saying about DreakTrek:

Tulsa Book Review says that DreamTrek: “…weaves through present and past, dream and reality…digs into…how complicated it can be to forgive and be forgiven…mysterious and suspenseful…”

“…mesmerizing and expertly crafted…” Lee G., 5-Star Amazon reviewer

“…first novel I’ve read by this author, but not my last.”, Harold S., 5-Star Amazon Reviewer

Kirkus Reviews calls it: “…clear, engaging prose…incisive and compassionate…subplots are equally well-crafted.”

For copies of DreamTrek visit: http://www.amazon./-/e/B007O46N0G