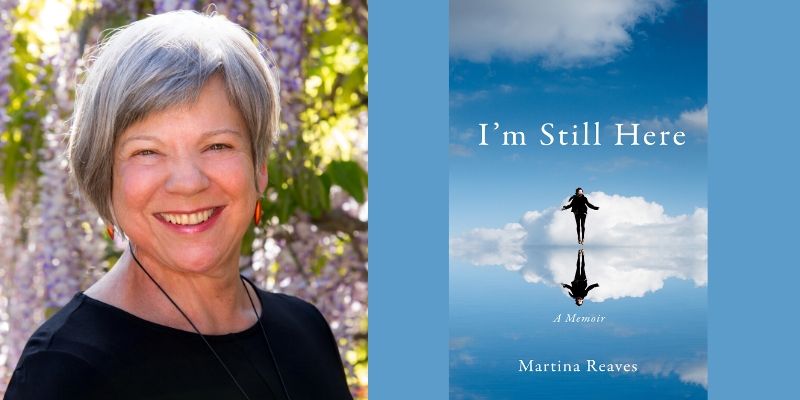

Martina Reaves grew up in a Navy family and lived in thirty-four places before she finally settled in her current home in Berkeley with her wife, Tanya, and their son, Cooper, who now lives in Oakland. She considers living in one place for over thirty years a major accomplishment. A lawyer who hated practicing law, she became a mediator in 1986 and worked with divorcing couples and neighbors with disputes. In 2007, she dropped writing legal documents and began writing fiction and memoir, and she has been at it ever since. Her memoir I’m Still Here debuted 4/21/20.

Why did you choose to move back and forth between different periods of time rather than a straightforward narrative?

I tried organizing the book in several ways: chronologically, in sections by time periods, and braided. I ended up braiding two storylines (the cancer odyssey alternating with my life story pre-cancer, starting at age twenty when I moved to San Francisco).

It turned out that the cancer story is heavier and darker when told chronologically. Mixing it up with the life story enhanced both stories. Although parts of the cancer story are difficult, as a whole, it’s full of moments of joy, humor, and intimacy, which are more illuminated when interspersed with the life story.

What advice do you have for readers who may be struggling with cancer diagnoses?

The most important piece of advice that I received was not to talk about cancer all the time. Before I received this tidbit of wisdom, I spent an inordinate amount of time talking to people about it, getting everyone’s advice about it, emailing about it, absorbing everyone else’s anxiety about it. The healer who gave me the advice told me to tell people I wasn’t going to discuss it anymore. After that meeting, I periodically sent group emails to update people on what was occurring medically, but I did not engage any further. You would be amazed how difficult it was to train people not to ask questions to try to get me to talk about it.

You often describe the natural world—trees, weather, ocean. How important has nature been to your healing process?

Being in nature has been very healing to me throughout my life. I find that it puts my life into perspective. I am, after all, just one dot of a sentient being in the midst of zillions.

At the moment, I’ve been sheltering in place almost seven weeks due to Covid-19. (My wife and I started early, before it was required.) Every day, I go outside around my house and in my backyard and relish spring: our wisteria, tulips, trees, bumble bees, birds nesting in our birdhouse. Once again, it doesn’t fail to lift me up.

You describe how, when people split up, other parts of their selves emerge, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse and they may seem “out of character”. Do you think this is equally true for other life challenges as well, such as being given a terminal diagnosis?

I believe a critical health diagnosis can definitely trigger dormant parts of a person to be expressed. The first time I had cancer, in 1981, our son Cooper was three months old. I’d spent the previous ten years in law school and getting established in a practice. My brain was finely honed, but my spirit had gone dormant. The cancer threw me into a more spiritual, emotional place in myself that was very different from my “lawyer” mind. When I healed, I transitioned from being an adversarial lawyer to being a mediator. My life was significantly altered by cancer then.

In 2009, when I received my terminal diagnosis following three gruesome surgeries and six weeks of radiation in the prior year, it felt like a bomb went off inside me. I closed my mediation practice. I dedicated my time to living, to spending time with family and close friends, and to writing. When I got well, I kept writing, but didn’t return to mediation.

Your memoir spans a wide range of emotions: humor, rage, despair, hope, patience, fear, confidence, love. Was it difficult to relive those feelings in the writing of the book?

This is a wonderful question. The answer is a resounding YES. There were times when I had edited the book line-by-line and needed to read it through. Sometimes, I simply couldn’t do it. I had to let it sit on the shelf for a few weeks to be emotionally ready to go through it again.

The back of the book states that “failing to die” is one of your biggest accomplishments. But isn’t living an even bigger achievement, fully embracing life?

It’s counter-intuitive for me to say this, but I found the few years after the cancer was gone to be more difficult in many ways than having the disease. When I thought I was likely to die––I never completely gave up––there was business I could ignore. Why have a fight with my wife? Why learn more technology? Why figure out the TV remote? The deferred maintenance on relationships, friendships, and myself took time and work. I kept feeling I “should” feel euphoric, but I was often overwhelmed and anxious, trying to figure out how to live again. And, of course, there was the waiting for the other shoe to drop. The medical establishment predicted that the cancer would come back for many months. Eventually, I came out the other side, happy to be alive, grateful for my health, my wife, our son, our community.

You appear to be a walking miracle—having been given less than 1% chance of survival.

When I was first given my terminal diagnosis, I wasn’t told there was even a minuscule chance I’d survive. I was told I was going to die and that death might be stretched to “double digits” of months.

My surgeon sent me to an oncologist for chemo, which was considered palliative care that might extend my life a little. But chemo, he told me, was not curative. It took my oncologist many months after the last chemo treatment to throw up his hands and say, “You know you’re unique, don’t you?”

“How so?” I asked. I thought lots of people got chemo and got reprieves from symptoms.

“Because we’re supposed to see and feel tumors all over your neck and face by now,” he said. “You had a less than one percent chance to survive.”

You’ve lived such a full life, often at the “cutting edge” (being a woman lawyer, a lesbian mother, etc.) What does your second memoir, in process, focus on?

In 2013, as I kept editing and working on I’m Still Here, I started writing what I then called flash memoirs, short pieces, sometimes just a paragraph, sometimes a few pages. When I’d get about twenty pages, I’d open a new “chapter” and continued until 2019, when I had fourteen chapters. I’ve arranged them into a book called Ebb & Flow. It deals with the ebb and flow of my life during these years and focuses on my mother’s aging, my complicated relationship with her, my own aging, and life’s little joys and aggravations. It ends with my mother’s recent death, just shy of 100 years, on January 23, 2020.

The book ends in 2015. How is your health now?

I’m a relatively healthy 71 and cancer-free. It’s been almost eleven years since my last chemo treatment. I’m profoundly grateful to have had these eleven years. In most ways, it’s been the best time of my life.

Read our review for I’m Still Here.