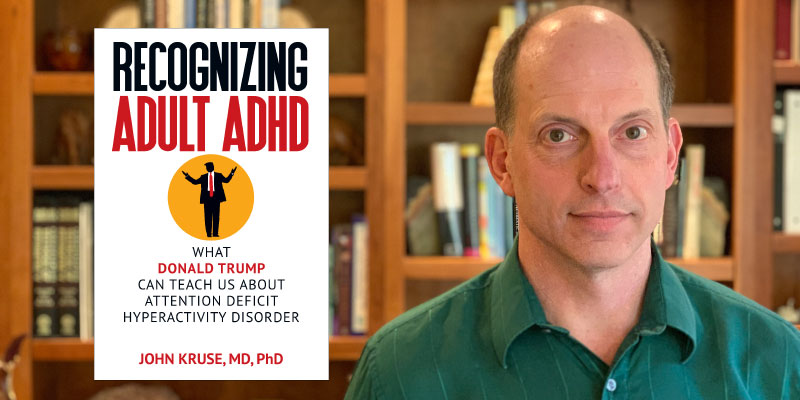

San Francisco Book Review’s Grace Utomo talks with Dr. John Kruse about ADHD and his book, Recognizing Adult ADHD: What Donald Trump Can Teach Us About Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

Why did you decide to specialize in ADHD? Do you only focus on adults, or do you also treat children?

The possibility that adults might have ADHD never came up once during four years of training at a respected psychiatry residency program. When I started my practice in 1994, the university referred me to a 40-year-old patient whom they had evaluated for ADHD. They reported that although he had robust symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, that he must have something other than ADHD, because “ that didn’t occur in adults”. After weeks of interactions, and discovering no other explanation for his behaviors and thought patterns, I realized that he did have ADHD. That launched me into studying the early research that indicated that actually only one-third of children with ADHD fully outgrow the condition. The more aware of ADHD I became, the more I recognized it in patients, which led me to specialize in the condition. I only work with adults but am currently treating individuals with ADHD ranging in age from 18 to 81.

You mention in your book that your adult ADHD patients first drew your attention to the similarity between their own symptoms and President Trump’s behavior. What prompted you to explore the connection further?

During the 2016 presidential campaign, one of my patients noted similarities between Mr. Trump and herself. They both demonstrated physical restlessness, a pattern of speaking whatever was on their minds, and a tendency to wander into peripheral topics. Along with this realization, she stated that the best thing that Trump could do for her would be “to come out as having ADHD”. She realized that he could help huge swaths of the public understand that ADHD was not a simple problem with inattention, but a pervasive and potentially destructive condition and that if more people in her life could have understood this, her own life would have unfolded in more positive ways. Her insight resonated with me, and I realized that we were in the midst of a vast and ongoing teaching opportunity.

How did your patients react when they learned you were writing a book based on their reactions to the president’s behavior? How many of them have read it?

Most of my patients, whether or not they have ADHD, have voiced interest in, and enthusiasm about my book. Some have read it, some have listened to the audiobook, and some have bought it and procrastinated on starting to read it. (This is largely an ADHD population, after all.) A few patients and colleagues have said that they were interested in the book, but found Mr. Trump so toxic that they couldn’t stomach reading a whole book about him.

Why did you decide to publish your findings as a book instead of as a journal or magazine article?

I’m interested in nuance, and in deepening my own and other’s understanding of a topic. Once I started digging into the topic of Mr. Trump and ADHD, more and more aspects seemed worthy of further exploration and explanation. The psychiatric publishing world shied away from such a politically charged topic, despite a wealth of studies demonstrating that we reduce stigma about mental health conditions and other aspects of humanity by discussing how they relate to individuals, not just faceless groups of individuals. Because I think that informing the public about adult ADHD is so important, and timely, (due to Mr. Trump), I have also been posting weekly articles on medium.com for the last forty weeks, about how ADHD illuminates aspects of Mr. Trump’s behavior, and how Mr. Trump puts a spotlight on interesting features of ADHD. I haven’t run out of new material yet.

Do you have any background in political science? If so, how did it affect your clinical analysis and writing process?

I have an abiding interest in political science, but no formal training. In college, I would surprise classmates by knowing more about their home state senators than they did.

You make a strong argument for diagnosing Trump’s ADHD without a clinical interview. Have you encountered other cases where adult patients were diagnosed without an interview?

The diagnosis of Trump’s ADHD depends on the confluence of two unique occurrences: 1) the criteria for diagnosing ADHD are purely behavioral descriptions, so we don’t need to know an individual’s moods, motivations, or internal thoughts, and 2) the public domain contains vast troves of readily accessible behavioral information for only a handful of prominent individuals, like Mr. Trump. The video evidence of Mr. Trump’s ADHD dwarfs what you could obtain from several hours of clinical interviews. This allows me to state with certainty that Mr. Trump fulfills the criteria for ADHD. We can’t achieve that level of confidence for other conditions for Mr. Trump, or for ADHD in most other people.

Your goal seems to be educating the general public about the disorder and encouraging potential ADHD adults to seek evaluation. While this is a bipartisan emphasis, your parenthetical remarks about the Trump administration and other conservative politicians seem to be left-leaning. Were you appealing to a specific readership?

My intended audience is four-fold: 1)those who don’t know much about ADHD, 2) those seeking a fresh perspective on ADHD 3) those who want to understand why Mr. Trump violates so many conventional norms, and 4) those who are interested in how our whole society is moving in evermore ADHD directions. I strive to discuss mental health issues, and Mr. Trump’s behavior, as objectively as possible, and anchor my statements in science and observations. However, the interpretation of the impact of some of Mr. Trump’s behavior will differ depending on one’s political perspective. I have tried to minimize, but not hide, my own political biases, and make it clear what is fact and what is interpretation.

Could linking adult ADHD to President Trump actually stigmatize the disorder, especially given the current political climate? What would you say to readers who might ignore their symptoms because they’re afraid to identify with the president?

A generation ago, he gay community debated whether outing individuals with sordid pasts (e.g. lawyer Roy Cohn, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, mass murderer Jeffrey Dahmer) stigmatized the gay community. Research indicates that we begin to break down negative stereotypes by knowing people from stigmatized groups and demonstrating that these are real, identifiable, individual human beings. Part of this process includes learning that these outed individuals have some traits that are generic to the group they belong to, and many many others, aspects that are specific to them and not group traits. Mr. Trump has ADHD. He is also male, right-handed, over six feet tall, more than seventy years old, and a native New Yorker. Left-leaning right-handers aren’t renouncing their own dextromanual status, because they know that right-handedness is just one feature they share with Mr. Trump, it doesn’t make them alike in other ways. Similarly, if some people with ADHD don’t like Mr. Trump’s politics, there is no need for them to reject their ADHD because there are probably a host of other characteristics that also distinguish them from the president.

Furthermore, as I emphasize throughout the book, ADHD informs us far more about how someone processes information than about the content of their minds. ADHD contributes mightily to the president’s blurting out whatever is in his mind but does not determine the crude, or racist, sexist, or anti-immigrant thoughts themselves.

One of my goals in writing this book is to help more people recognize their own ADHD because millions of Americans who have it are not aware of it. Those with ADHD tend to be less aware of how they appear to others, and of their impact on others. Using Mr. Trump as the poster boy for ADHD can guide more of these individuals with ADHD to self-awareness. Failure to recognize ADHD remains a huge barrier; after attaining this recognition each person will have their own journey to find further appropriate information to help them to function more fully and effectively in the world, whether that involves engagement with the mental health system or not. I hope that my book makes a compelling case that various therapies and medications may be useful in addressing ADHD, but everyone should be free to choose how quickly they travel the path from discovery, to learning about options, to finding life options that work for them.

How do you believe the chapter on coping with President Trump helps friends and family view ADHD positively? Is there a chance readers might interpret that to mean their loved one’s diagnosis threatens their own mental health?

We currently consider ADHD a mental health disorder because it does cause problems, both for individuals with ADHD, as well as for some of the people in their life. That doesn’t mean those with ADHD can’t be loving, passionate, interesting, fun people. When ADHD goes unrecognized it still causes dysfunction and distress. Worse still, behaviors invariably are misinterpreted if ADHD goes unidentified. Individuals are labeled careless, lazy, self-centered, erratic, crazy, or ill-tempered, and attempt to “cure” these problems are doomed to failure if the source of these behaviors is misdiagnosed. Every couple’s therapist knows that ADHD affects social lives as profoundly as it disrupts educational paths or careers. This highlights why we make diagnoses – to understand, to predict how a condition will evolve if untreated, and to suggest appropriate treatments (which does not just mean medications).

Your patient anecdotes highlight ADHD treatment options and offer inspiring examples of adults who overcame significant challenges to enjoy successful lives. Would you ever consider re-releasing this book as two separate books: one about health education, and the other about politics?

My book would probably be either to pitch to publishers or editors if the information about ADHD was separate from insights into Mr. Trump’s behavior. Excellent books on ADHD already exist, but only those with ADHD, or a strong suspicion of it, read them. I wanted to reach out, using Mr. Trump, to those who might never read a self-help or psychology book. Combining these topics generates opposition from organized psychiatry (for delving into politics), ADHD groups (for tarnishing the label with Mr. Trump), those on the left (for exonerating what they perceive as the president’s bad behavior) and those on the right (for pointing out unattractive traits). But I also have received support from mental health workers, who have used the book to educate their patients, or who said that they themselves had missed Mr. Trump’s ADHD because they were so consumed by his apparent personality disorders. And individuals with ADHD have praised the book because they felt that it offered some new insights and analyses about the condition not available in other books or blogs. And I have heard from leftists who appreciated how my book made Mr. Trump more comprehensible, and by those on the right who realized that ADHD was both more accurate and less pejorative than the critics who label the president a baby, tyrant, or idiot.

ABOUT JOHN KRUSE, MD

John Kruse, M.D., Ph.D., is a neuroscientist, psychiatrist, and author of the book, Recognizing Adult ADHD: What Donald Trump Can Teach Us About Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. With 25 years of psychiatry experience, Dr. Kruse specializes in treating adults with ADHD. For more information, please visit www.drjohnkruse.com.

Dr. Kruse grew up in Shaker Heights, Ohio, where he received an excellent public school education, winning national awards in Latin, and writing. The Future Scientist program at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History heightened his passion for biology and the natural sciences through activities including banding hawks and owls, traveling to see thousands of migrating Sandhill Cranes, collecting snakes and turtles in northeast Ohio.

After graduating Phi Beta Kappa and summa cum laude from the University of Rochester, he remained in Rochester to complete his medical degree and to earn a Ph.D. in neuroscience with a dissertation on circadian rhythms. While at Rochester he also helped design early research using bright lights to treat Seasonal Affective Disorder, and he assisted in establishing and editing The Journal of the University of Rochester Medical Center. He moved to San Francisco in 1990, completing a psychiatry residency at UCSF and receiving an Outstanding Resident in Psychiatry award from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Kruse realized that his strength as a psychiatrist lay in his ability to think about and help individuals with mental health conditions at multiple levels ranging from brain chemistry to whole-body health, to intra-psychic, interpersonal and socio-political aspects. He consequently nurtured a practice where he continues to employ a variety of therapeutic approaches. In addition to direct patient care, he has taught basic psychopharmacology to psychotherapy interns for 25 years and has spoken at local, state, and national psychiatry conferences about gay marriage, gay families, and the biology of emotions.

In 1994, one of his first patients, a man in his mid-forties with classic ADHD symptoms who had been told that adults couldn’t have the condition, launched Dr. Kruse on the road to learning more about adult ADHD. More than 300 patients over the next 25 years contributed to furthering this journey, teaching him how to recognize ADHD; treat it effectively with talking therapies, medications, exercise, diet, and meditation; and help patients deal with partners, families, co-workers, and teachers who did not grasp how ADHD affects individuals. For the last decade, Dr. Kruse has supplemented his direct clinical knowledge by being a member, and eventually, co-leader, of a local group of psychiatrists focused on treating adult ADHD.

When he’s not treating patients, John is an avid runner who has completed 100 marathons. He also trained several hundred novice runners to complete a marathon while coaching for the AIDS Marathon Training Program. For over a decade he was an editor and columnist for The FootPrint, San Francisco FrontRunners’ monthly newsletter. John and his husband are parents of thriving twin teenage girls. He continues to enjoy birdwatching, nature photography, gardening, and baking.