Lessons in Gravity is a new-adult novel set in Yosemite National Park. Seeing as the park is just a few hours’ drive from the San Francisco Bay Area and north central California cities, many of us who live locally have a special connection to the park and, along with visitors from around the world, name it as one of our favorite places on earth.

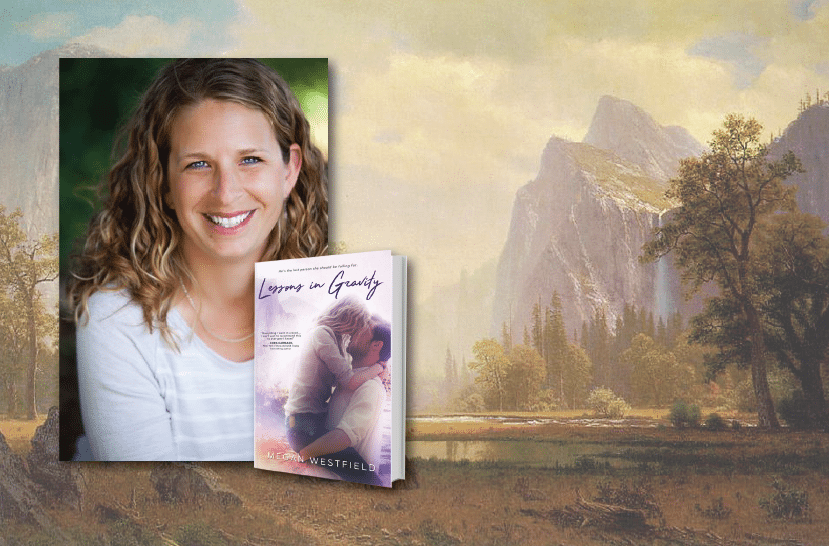

San Francisco Book Review‘s owner, Heidi Komlofske-Rojek, sat down with their former book reviewer and new author, Megan Westfield, to talk about her book.

What prompted you set a book Yosemite?

Early in our lives together, my husband in I lived in South Lake Tahoe and would go down to the park as often as we could to rock climb. Those trips were so important to me, getting to spend so much time in the incredible beauty of the park, and getting to experience it as somewhat of a regular, where you’re seeing it in all seasons and it’s not a rush to get everything in because you’ll probably be back next weekend, too.

So the rock climbing focus of the book was also a result of those trips?

Definitely. Yosemite has always been an inspiration to writers, but being a commercial fiction writer—not an esteemed nature essayist in the vein of John Muir—I was fascinated by the modern operations of the park in addition to its wild backcountry spaces. And what better represents this than the park’s storied rock climbing history and culture? Additionally, experiencing the park from the side of one of its formations is quite different than seeing it from an overlook where you have two feet planted firmly on the ground. Most of the park’s 4 million annual visitors don’t have a an opportunity to experience this firsthand, so I wanted to somehow share a little piece of that.

Did the lawsuits regarding the trademark of Ahwhanee Lodge and Curry Village and other Yosemite place names affect your book?

I started writing Lessons in Gravity long before this lawsuit and remember being so upset when I first read about it. (In short, after losing a 15-year hospitality contract renewal, a former concessionaire wants to charge the park $51 million for the trademarks of the names of dozens of beloved sites in the park.) The National Park Service can’t—and won’t—bend to this demand, and had to stop using the names in question as of March 1, 2016. I had somehow missed the news of the name changes actually happening and didn’t learn about it until August, when the book’s copy editor picked up on the name discrepancies.

Currently, it seems there is still hope of legal action that will allow Yosemite National Park to retaining the historical names, so I decided to keep the historical names in place in the book. I would guess that most people in the park still refer to the landmarks by their historical names, so it makes sense that my characters would be doing the same thing when thinking or talking about these places.

When I was in Yosemite Valley, I didn’t see a Sorcerer Spire.

Sorcerer Spire is fictional.

Why did you decide to create a fictional version of something when there are so many real formations you could have used?

You’re right, I could have easily had Josh’s big free solo climb be on one of the well-known formations like El Capitan or Half Dome, but between the time I started plotting the book and when I got through the second draft, there had been very notable and widely watched films of real-life climbers doing just that. I wanted Josh’s climb to be something that hadn’t been done before, something that people doubted could be possible. Another problem is that all of Yosemite’s actual formations are so beautiful, but I wanted to Josh’s formation to be darker and uglier, a little bit sinister. In my mind, I see Sorcerer Spire as a combination of Angel’s Rest in Zion National Park and something like Sentinel Rock in Yosemite Valley.

What about Flying Sheep Buttress and Lake? Are they real ?

Flying Sheep Buttress and Flying Sheep Lake are also fictional. Tuolumne Meadows is a very special place to me, and with the book being set in the early spring when the roads to that section of the park are usually closed, the characters never go up there. Instead, I brought a little piece of what Tuolumne Meadows down into the Valley.

Sports romance seems to be gaining popularity these days. We see lots of hockey, football, and MMA come across our desks, but this is the first rock climbing novel we’ve seen. Do you think adventure sports will draw the same readers as traditional sport books?

I hope so! Rock climbing as an endeavor and as a competitive sport is inherently different than the sports that are nationally televised in the United States, but some of the core elements of these sports stories are the same. In an adventure sport novel, readers will see much more focus on the playing field (the spectacular natural environments in which these sports are happening), and the level of danger is much higher. With adventure sports, there is typically not a full medical staff standing by just a few feet away at all times; if the athlete is somewhere remote, they could be a day’s travel from the nearest hospital, or dependent on a search and rescue helicopter. That is, if the terrain can even support such a rescue.

There’s a lot of technical climbing terminology in the book—how did you balance adding genuine flavor without losing the reader in jargon?

Climbing words are fun and I wanted to use as many of them as I could in the book. Of course, I had to reign myself in during the editing process. I did this by being consistent about which term I was using for things that have multiple descriptors, such as always using the word “ascending” when there is also the word “jugging” that describes the same action of climbing up a rope.

Like Kleenex® and Band-Aids®, some types of climbing gear have a commonly used name that is actually is a specific brand’s take on that piece of gear. Grigri®, for example is Petzl’s line of belay devices. Camalots® are Black Diamond’s line of camming devices. In some cases, my editor recommended removing words completely. The word “choss” comes to mind. It’s a word that climbers use to describe poor quality rock—the kind of rock that might crumble in your hand as you pull on it. It’s not in the dictionary, and in the place where I’d used it, it was hard to tell what it meant by context, so I ended up taking it out of the manuscript.

BOOK EXCERPT

Madigan started the van and eased it through the parking lot’s deep potholes and onto the main road. Within a minute, they broke through the shadows of the forest into a breathtaking meadow surrounded by cliffs as tall as skyscrapers. April was transfixed.

Rounding a corner, they came face-to-face with a cliff so massive that she gasped before she could stop herself. The monolith jutted into the meadow like the curved bow of a ghostly Titanic returned to this world even larger than it had been in real life.

“That’s the captain,” Madigan said. “El Cap-e-tan.”

She followed the edge of the buttress from the ground, up, up, up to where its angular profile met the cloudless sky. Madigan watched her reaction. “Amazing, isn’t it? That’s a lot of granite. Look behind.”

Through the side mirror, there was a clear view of the head of the valley: a supernatural amphitheater of warm gray cliffs, with one particularly remarkable, sheer-sided dome perched high above it all. To complete the panorama, there was a shimmering waterfall dropping from the tops of the cliffs to the valley floor. Now, this was sublime.

Ahead, the meadow was wider, with a creek running through the center and a deer and fawn grazing along the banks. The sun was still behind the rim of the valley, but its rays were beginning to separate and bend over the cliffs.

“Stop!” April cried.

As Madigan pulled onto the shoulder, she unzipped her camera bag and unbuckled her seat belt. She threw the door open and raced into the meadow, only vaguely aware of the muddy water flying up and soaking through her jeans in icy little pinpricks.

In the middle of the meadow, she halted and lifted her camera. Slowly, she turned in a circle, holding her breath to steady the shot. Sunbeams poured over the rim, fanning into a thousand rays of golden light that reached down into the meadow. Her mind was going to explode from the beauty of it.

She completed the pan as the top of the sun itself appeared, thrusting the valley into a gorgeous patchwork of shadows and brights that would be too much contrast for her camera.

“Sorry,” she said when Madigan caught up to her. “I got a little excited.”

“No—that was awesome! Did you get the shot?”

“I think so,” she said. She replayed the footage for him. “It would have been better with a Red Dragon.”

“Looks great to me,” he said.

They sloshed back through the meadow, toward the van and the base of El Capitan.

“There are some climbers up on Pacific Ocean Wall.” He stopped and pointed. All April could see was rock, rock, and more rock.

“They’re like pinpricks. Look for shadows. See there—right above the tree line?”

April stood behind Madigan’s pointing arm, straining her eyes to pick out a miniature human. She couldn’t see anything.

“Try your camera,” he said.

Even zoomed in all the way, she couldn’t see any people on the wall. Then, in a sunny patch, she spotted a hair-thin black bar that didn’t look quite natural. There was a crumbsize lump on top of the bar and a black speck no bigger than a newborn spider hovering on the rock above it.

“The belayer’s still on the portaledge,” Madigan said. “It’s probably their first pitch of the day.”

“They spent the night up there?” She squinted. “On that little thing?”

“It’s actually eight feet long. Yes, it’s small, but when you’ve been standing on buttonheads all day, it feels pretty big.”

We encourage you to pick up your copy of Lessons in Gravity at your local bookstore. Support indie bookstores. They need our money more than Amazon.