By Jeanie Kortum, author of Ghost Vision and Stones

Kenya, 1984. I first knew the cutting was close when the sun rose and the young girl who had been dancing all night, bleating through a whistle, was dragged across the clearing by an old woman and lowered to the ground. All around her, women fell to the ground, emitting strange cries. The old woman held a piece of glass in her hand. The men sitting around the fire drinking from large calabasas, turned away.

The whistle in the young girl’s mouth was replaced with a stick so that she would not cry out and curse the ceremony.

When the cutting happened it was quick, grubby and gynecologically matter of fact. The old woman turned and dropped the clitoris onto a leaf. The stick had worked. Though the little girl’s legs were shaking and her eyes leaked tears, she hadn’t cried out.

When I went to visit her a little later someone had piled a small hill of maize on her wound. Transfixed, I watched as small tributaries of blood leaked into the white flour.

That morning, as if I too had a stick in my mouth, I withdrew into the comfortable objectivity of North American scrutiny: I too did not cry out. For thirty years I have carried the shame of that moment, whatever I could have done to stop the proceedings, sealed forever in the resin of my silence.

It had begun as a brave dream. I was going to do a series of books about endangered cultures. To research the first, I dogsledded to a village at the top of the world in Greenland and lived with the Inuit. That book easily sped out of me. To research the second I lived with a hunter-gatherer tribe, then went back for a second year with them and witnessed the clitoridectomy.

Thirty years ago, FGM was not the cause célèbre it is today. I returned to San Francisco and began to write. Draft followed draft, finding what I wanted to say elusive. One draft was too shrill, a political diatribe; another sodden with poetry; yet another so mystical it disappeared at the edges and even I didn’t understand it. And always the questions: How could I possibly juxtapose my privileged American life against a ritual so ancient that it’s been discovered on mummies from the 16th century BC? Could a woman living in North America possibly understand the economic and political realities that factor into this decision? Did I even have the right to write this book?

I did not want to narrate the world through the dirty window of prurient exploitation, nor did I want to write an angry book. I wanted to explore the trauma of FGM with beautiful language, write a story so powerful it would marry the intricate properties of poverty and exploitation with words that would shrink the world, reminding us that we belonged to each other. But how could I possibly do that when the story’s centerpiece was about cutting a woman’s vagina?

As I said, a brave dream.

Draft after draft sputtered out. Months turn into years. I could not unlock my words and give myself permission to enter another woman’s life, narrate her joys and laments. I soon realized I was living the silence and despair of a crippling writer’s block.

In the end what led me not only to the words of this story but into the next part of my life was a little four-year-old girl, Crystal, and Sandy, her drug addicted mother prostituting herself on the streets of San Francisco. The year was 1986. To combat the silence of writing I began volunteering in one of the city’s most impoverished areas. Every Friday when I went down to volunteer, two little girls were on the same street corner by the Kokpit bar, panhandling for change. One day I walked across the street and asked if they wanted to come into our program.

“Acute bronchitis,” the doctor said when I took the little girls in to see about their severe coughs and that fact along with the knowledge that the older sister was not yet in school compelled my husband and I to report them. We were made emergency foster parents and then the girls were placed with their aunt Bessie. Two weeks later Bessie called, asking us to take them. We only had the resources to take one, so the day before kindergarten started, Crystal walked up the path to our house, all of her belongings in a big plastic bag.

A couple of years after we had adopted Crystal, I received a call from Sandy. She wanted to see her daughter and we arranged to meet at a park. We sat on a bench, making small talk and watching Crystal ride her new pink bike, Sandy too skinny, clearly nervous. “Look mom,” Crystal said wheeling by with no hands. “Good job,” we both said, then looked at each other and laughed— Sandy the mother who despite her terrible drug addiction had tried to keep Crystal safe and me charged with shepherding Crystal into the next part of her life—past and future, our bargain sealed with a laugh on that park bench.

Then, several years later, a terrible phone call. Sandy was at San Francisco General Hospital, 36 years old and dying of emphysema. Once more, she wanted to see her kid.

In the year and a half it took for Sandy to die, Crystal and I visited her just about every week, often more. Crystal easily embraced us both. “Two moms to love me more,” she said. Sandy never once sabotaged my relationship with Crystal. We both knew that beneath our teasing a holy covenant was being signed: She was giving me her daughter, giving me as well the responsibility for remembering.

When I told Crystal that her mother had died, she pushed her head into me as though wanting to climb inside. That afternoon we went to get Sandy’s things. It was only one small suitcase, inside two neatly folded sweatshirts, some coupons for coffee cups and glasses, a stuffed animal that Crystal slept with for many years, an old arrest record with a photograph of Sandy crashing hard, eyes metallic. Unable to sever this final umbilical cord with her mother, Crystal stroked her hands across these few items left of a life, then began to cry.

Understanding for the first time on a deep, visceral level how a childhood bereft of hope can lead one directly into the oblivion of drug addiction, I turned to helping other Sandys. I approached the Park Service with an idea. Could there be a cottage out on the coast where homeless children could experience a sense of home, dip their feet in waves—some for the first time—escape the brutality of the streets, if only for an afternoon? The Superintendent agreed, telling me to go pick a house. It was a little cottage with a glass porch overlooking the ocean. The kids designed it. “We want a fruit bowl, a clock that ticks, and yellow walls,” they told me.

That one house blossomed into four sites, five different programs, a budget that nudged up to a million dollars, a staff, a board, hundreds of kids and volunteers.

One of the programs was family drop in, where women gathered to cook, plan birthday parties, hang out with their children, in short celebrate the ordinary family events that can’t happen on the street. Once, we even had a wedding in the backyard. All colors, all shapes, all backgrounds gathered inside the butter-yellow walls, women like Sandy who had fallen into drug addiction, women who were mentally ill, on the run from abusive husbands, women who were here illegally and could not find work.

It was a sweet culture where pain and longing was understood, a place where every life mattered and we could tell our stories (myself included—I was going through a divorce from someone I deeply loved). It was here we could acknowledge our brokenness, begin to repair, rebuild, get started again. Reaching through the veils of our differences, we warmed our hands on a common hearth because inside those yellow walls, that which made us the same mattered more than our differences; we were all mothers and we all loved our children.

And the stories the women told were horrendous and cruel. The delicate woman with enormous eyes who had just escaped a firebomb her husband had thrown, igniting the house, herself, and her son. The mother, so traumatized she could barely talk, who sputtered out the story of her ex-husband who had hung her little boy from the door ledge, laughing gleefully when he finally dropped.

I began to understand the link between poverty, homelessness, and FGM, the desperate choices women have to keep their children alive. If you live in a small hut with nine or ten children, wouldn’t you do just about anything to keep your children alive, even if what you have to do is bend between your daughter’s legs and cut her genitals in order to qualify her for marriage and payment of a dowry? The woman on the street who chooses to live in her car because her husband has started to slip into her daughter’s bedroom late at night… both are desperate acts born of poverty, so crafty and well designed they are perpetrated not by the oppressor but by the oppressed themselves.

A door opened and a gigantic voice honoring love and survival blew in. Incubated in all those years of silence, all the stories of all the woman I knew were braided into this new voice of mine. Finally I was becoming strong enough to write a story that pressed the tremendous hurt of FGM against the grave beauty of being alive.

A three-dimensional heroine stepped forward, schooled in feminism but brave enough to surrender to an ancient mystical belief system. A study in opposites—old yet modern, linear yet intuitive—her contrasts rasped against each other like flint, sparking fire. Many mornings, savoring for the first time my own opposites, I rose to write in that light.

I was beginning to understand. This book had been waiting for me for all these years, waiting for me to become a woman large enough, receptive enough to hear its story. The only way to write it was to become more: more brave, more vulnerable, hazarding, risking, leaking the tears for our daughters down into my words, dreaming a beautiful dream of wholeness for all women.

After 18 years I retired from A Home Away from Homelessness to wander the hills of Marin and finally finish this book. In the span of time it took to write it I would fall in love with one man, get divorced, fall in love with another man, adopt two kids, inherit a new batch of stepchildren, lose my parents. Five presidents, the advent of computers and AIDS, the dissonance of life itself…but what remained constant was this book, as I woke every morning to write in its light. As if sculpted from time itself, the story often seemed like an ancestral memory, reminding me of something I had almost forgotten. I sometimes felt more like the book’s scribe than its author.

Sustained by the miracle of the children I have adopted from terrible circumstances now living healthy lives, Sandy’s enormous courage, the homeless mothers and children I have met who—despite hunger, sexual and physical abuse, and insecurity as immediate as not knowing where they’re going to sleep—still manage to live days filled with hope and possibility… I was finally beginning to write the book I had always wanted to write.

To this day I don’t know if there is a common woman’s experience, but I do know we are linked as women because we have the same anatomy. Vaginas have no passports. FGM cuts away the only organ grown by women just for their pleasure. This sordid act of amputation transcends the artificial barriers of geography, class, age, and race. Lurid with hate, this practice, so eloquent with misogynist dread, moves across all those continents and arrives ringing to each and every woman. “You are wrong,” is the dictate all those mutilated vaginas have absorbed. “Your sexual appetite is wrong, your sensuality and ardor is wrong. We will cut off the berry of your clitoris, slice your labia minora and labia majora, bury the cut parts of your body beneath the dirt. Make yourself tidy, submissive, and mine.”

Girl, woman, mother and now grandmother, the more I deepen into the assignment of womanhood, seasons notched by my own story, the more I understand the seriousness of what has been cut away. Both home for the seed of life and the spill of longing, those private undulant lips serve as a gateway for new life, shelter the source that began us all.

In the 30 years it is taken to write this book, FGM has entered our global conversation. Finally this ugly crime is rinsed with hope. The United Nations has adopted a call to ban FGM worldwide. Countries are outlawing the practice; activists, tribal women, academics, and politicians from around the world are beginning to collaborate to stop this terrible practice. All those girls delivered trussed, sewed, and paired to a man, the entombed light of sexuality forever stitched inside of tattered vaginas—no more!

A well-written story can cross the artificial barriers of geography, race, nationality, and class and cause the entire web of womanhood to shiver. If done well, the story should solicit the question how would I survive the circumstance, what would I use to keep alive, and then what may be the most militant question of them all: If they are me and I am them, how can we together resist?

I know I will be criticized for this book, but I believe that political correctness, the notion that we can’t speak for another living on a different continent, is merely a license for not caring. I know as well the personal price that silence extracts. If our literary productions are different from our women’s speech, culture itself becomes part of the falsehood.

There is a drumbeat sounding around the world: women are gathering to tell their stories and stop this terrible practice. “No more cuttings,” women are saying with one voice. “No longer will we be silent, our silence serves only those who cut. No more dirt fertilized with women’s parts. We will speak with one voice, our hearts open in sisterhood.”

“We are human, we are women. Ardent, moaning, praying, crying, kissing and playing, singing the music of our sighs, we want to live full, sensual lives speaking with all of our parts. No more cuttings, no more blood, this is our incandescent song for sisterhood.”

And finally this North American woman can raise her voice and sing as well.

AUTHOR BIO:

Jeanie Kortum is an award-winning author, journalist, and humanitarian. In partnership with the National Park Service, she founded A Home Away from Homelessness for homeless children and served as its Executive Director for nearly twenty years. Her philanthropic work has been widely recognized by a long list of awards, including the Jefferson Award, the San Francisco Foundation’s Community Award, the Commission on Women Making History Award, the Espiritu Award from the Isabel Allende Foundation, and the 2006 Lifetime Achievement Award from the San Francisco Urban Research Association. She has been the subject of two CBS national news profiles and rights to her life story have been sold to Warner Brothers.

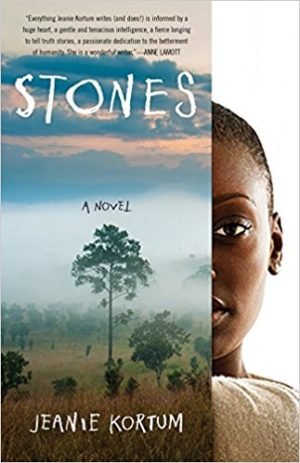

Kortum’s award-winning first novel, Ghost Vision, is loosely based on her experiences living at the top of the world in a Greenland village. She researched Stones by living with a hunter/gatherer tribe in Africa, during which time she witnessed a clitoridectomy. This experience compelled her to bring awareness to Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and assistance to young women forced to undergo the procedures. Stones will be published in July, 2017.

Kortum lives with her husband and adopted son in Northern California and Ireland. Visit: https://www.jeaniekortum.com